by Lily Applebaum

Joyce Carol Oates has been publishing work, essentially without cease, since the year 1964 when she published her first novel With Shuddering Fall. Her chosen forms range from novel to short fiction to poetry to literary journalism on boxing (On Boxing). She is famously prolific, and famously centered on a few recurring themes: insanity, rape, deteriorating relationships, deteriorating social status, crime, drug use, domestic life. She is clearly well-read and well-versed in the, particularly American, great books, and acknowledges such influences on her work with her book Wild Nights! There, Oates does show her wild side, an experimental short fiction collection where she tries on the writing styles and personae of the five writers whom she admires or who have influenced her writing: Poe, Dickinson, Hemingway, James, and Twain. Oates obviously has a true passion for and dedication to daily writing, an act she must engage in obsessively to produce her average of two books per year. These facts as presented about Oates’s writing practice make contemplating her use for Twitter daunting. How could someone who writes long sprawling novels with very clear thematic and narrative goals, or carefully crafted short stories, utilize such a disjunctive and constrained medium?

Oates said of her novel Childwold in a Paris Review interview about her writing:

I had wanted to create a prose poem in the form of a novel, or a novel in the form of a prose poem: The exciting thing for me was to deal with the tension that arose between the image-centered structure of poetry and the narrative-centered and linear structure of the interplay of persons that constitutes a novel. In other words, poetry focuses upon the image, the particular thing, or emotion, or feeling, while prose fiction focuses upon motion through time and space. The one impulse is toward stasis, the other toward movement.

I glean from this statement that Oates is primarily concerned with symbol, theme, immersive characters and linear narrative. Carefully creating and embodying characters that drive the plot. And these things she does well — not to my taste, but I would say, well. Childwold is not one of her novels that I have read, so I truly can’t speak to how well she achieved her intended goal of merging the poetic and the prosaic. However I have had the experience of reading another of her long novels, We Were the Mulvaneys, and more of Oates’s work (although what probably amounts to a piddly percentage of her body of published work) for the Fellows Seminar at the Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania, where she visited and spoke with my class in Spring of 2010.

I can say with confidence that I will probably never read another book or story that Oates publishes in print — but I will read every single thing she publishes on Twitter.

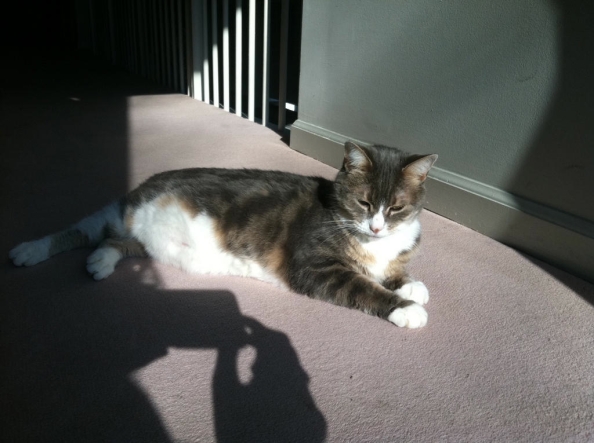

It is, admittedly, difficult to compare what Oates does with a 450 page novel like We Were the Mulvaneys with what she does with a less than 140 character tweet. Take one example of a recurring image in Oates’s books — the cat. Either feral, domesticated or, in the case of We Were the Mulvaneys, barn, cats roam freely through Oates’s landscapes and characters’ lives. Sometimes they are objects of tender affection, sometimes symbols of the wild part of us that always remains un-tameable, sometimes a metaphor for the trapped housewife as the cat also roams its sealed domestic world. Oates herself is a known cat-lover. So how do cats come up in her Twitter writing? The answer is: frequently. But the example that best illustrates the difference in Oates’s Twitter cat writing and her published cat writing is the following picture that Oates tweeted without caption on December 2, 2012

In the shadow we see Oates herself, her small hand holding up the phone, the outline of her curly hair just peeking around what seems to be the corner of a wall to photograph the cat. Here the cat isn’t presented as any kind of pre-packaged or carefully, consciously-wrought symbol or metaphor for anything. It’s a portrait of her cat, a representation that manages to be as self-aware as any twitpic could be. We can’t but look at this image and admire the cat but simultaneously contemplate the photographer. We see her role in creating the picture as much as we see the cat itself.

Oates does things with her writing on Twitter that in her fiction she would never dream of doing. In her published work, she’s concerned primarily, it seems, with mastery and careful use of linear motion, literary devices, progression, beginnings middles and ends, in a way that much experimental fiction is not. But most tweets are not like that either. Twitter is a place where this writer otherwise interested in creating a seamless immersive product is willing to show her process and resist narrativizing and creating symbols.

Posted on April 11, 2013

0